There is a video doing the rounds on the internet. It shows a department store with no employees. All consumers have an Amazon pay account which enables entry. As a product is purchased, the payment is automatically debited to their account. An AI algorithm then maintains an inventory update and registers consumer preferences for replenishing stocks. Obviously an ultimate in efficiency in terms of marketing, production management and technology. In terms of production, then, technology is not subject to any limits today.

A second strand of thought is how the focus of many international managers is on India. “India is one of the major and priority markets” (Renault’s CEO & MD, Venkatram Mamillapalle); “India remains top priority in terms of investment” (Cisco senior vice-president Kelly Jones); “About 200 American companies are seeking to move their manufacturing base from China to India post the general elections” (a top US-based advocacy group). Authors like Ruchir Sharma have also argued that no country can grow faster than the rate of growth of its population. Since India has a large population where at least the consuming cohorts are growing for the next decade or so, the focus of global managers seems justified.

Yet, the data is confusing. Even in a fairly developed metro like Delhi, the minimum salary, on average, in the organised sector is about Rs. 16,000 and that in the informal sector would be about Rs. 10,000 per month. It is probably lower in smaller cities. While the size of the population is large, where is the purchasing power if India is to drive global growth?

Interestingly, economic theory also seems to have no answer. It is a fact that since 2008, the world economy has been on a limited growth path despite massive “pump priming” of expenditure by the USA, China and other governments in a typical Keynesian response. Yet, post the pandemic, there is little expectation that global GDP will grow beyond two per cent per year (even these estimates of IMF/World Bank have been shown to be wildly optimistic in 2016-2018). Japan, most of Europe, New Zealand, or for that matter, now even China, which have been suffering from prolonged recessions, are countries with either ageing or declining populations.

So here is the conundrum. In developed countries, with the USA as the clear technological leader, technical change, particularly with advancements in AI, seems to indicate no limits on income and production. On the other hand, the future seems to lie with countries like India with large populations but with limited purchasing power. So then why has the world been stuck in a global recession since about 2008?

The answer lies in an anomaly in the Economics discipline. In an economy-wide focus (economists call this “general equilibrium”) all resources of capital, labour, etc. combine to produce all goods and services. Technology then acts to boost productivity hence removing the limits set by resource constraints. On the other hand, a study of consumer demand (so-called microeconomics) reveals that consumption depends on an individual’s income, and only “labour” consumes. Herein lies the problem.

It is critical to note that consumption requires not only income (as Keynes rightly stressed) but physical time. Purchase of consumer goods is useless if one does not have the time to consume - how many houses, phones, etc. can one person actually “consume”? Thus, if the population is stagnant, and the increased production is to find consumers, technology must necessarily be time-saving. Empirically, this has been seen in North America and West Europe where since the 1980s, much of the technological development has been in time-saving technologies like pre-cooked food, while saving time in sectors like electronics has worked through convergence: for example, the same phone is now a communicating device, a calendar, gaming console and a television, etc. Thus, the demand growth in such economies depends on the extent to which technology could be time-saving. (These results have been formally derived in the B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics, Feb. 2023).

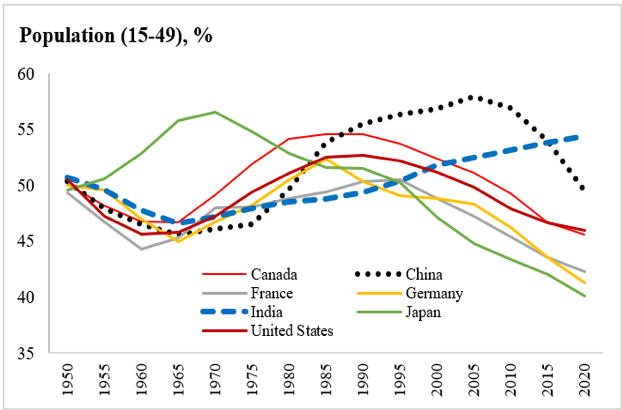

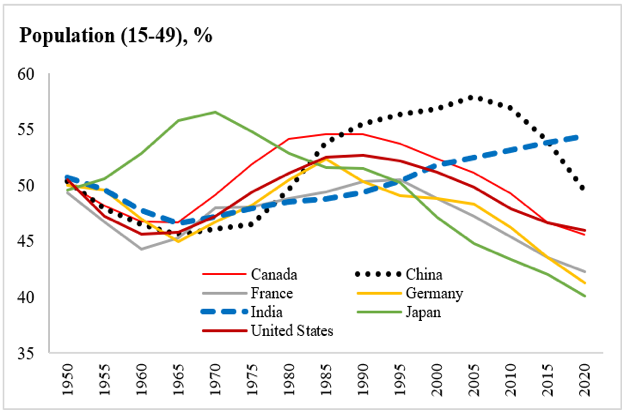

Yet, time-saving technology is not sufficient to solve the problem. With consumers having access to only 24 hours a day, there is a limit to which technical progress could be time-saving. This implies that while time-saving technology could deal with the asymmetry on the production and demand side to some extent, it cannot offer a long-term demand-supply balance. This calls for two possibilities. One, shifting consumers to where the income is generated or, advanced technology is available, i.e., allowing for immigration (a political no no!). Second, shifting the production base to where consuming cohorts are in abundance via FDI which combines production, technology and global sourcing of resources – this is why EMEs (especially India) matter! The accompanying chart gives some idea. The “young workforce”, which consumes approximately thrice as much as the older cohort, is rising in India, while it has been falling in developed markets, and even in China now. These trends are normally irreversible in the short to medium term.

Returning to the Amazon store example we started with - in this “technological miracle”, what if no one was there to enter the store? The limits to growth seem to lie not on capital and technology but on people. So (with due apologies to Marx) “people of the world procreate, you have nothing to lose but global stagnation!”

Prof. Manoj Pant is a former Dean/SIS/JNU and Vice Chancellor, IIFT. Currently he is a Visiting Prof. at Shiv Nadar University.

Dr. Sugandha Huria is an Asstt. Prof., IIFT.

💬 Comments

Share your thoughts on this policy

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!